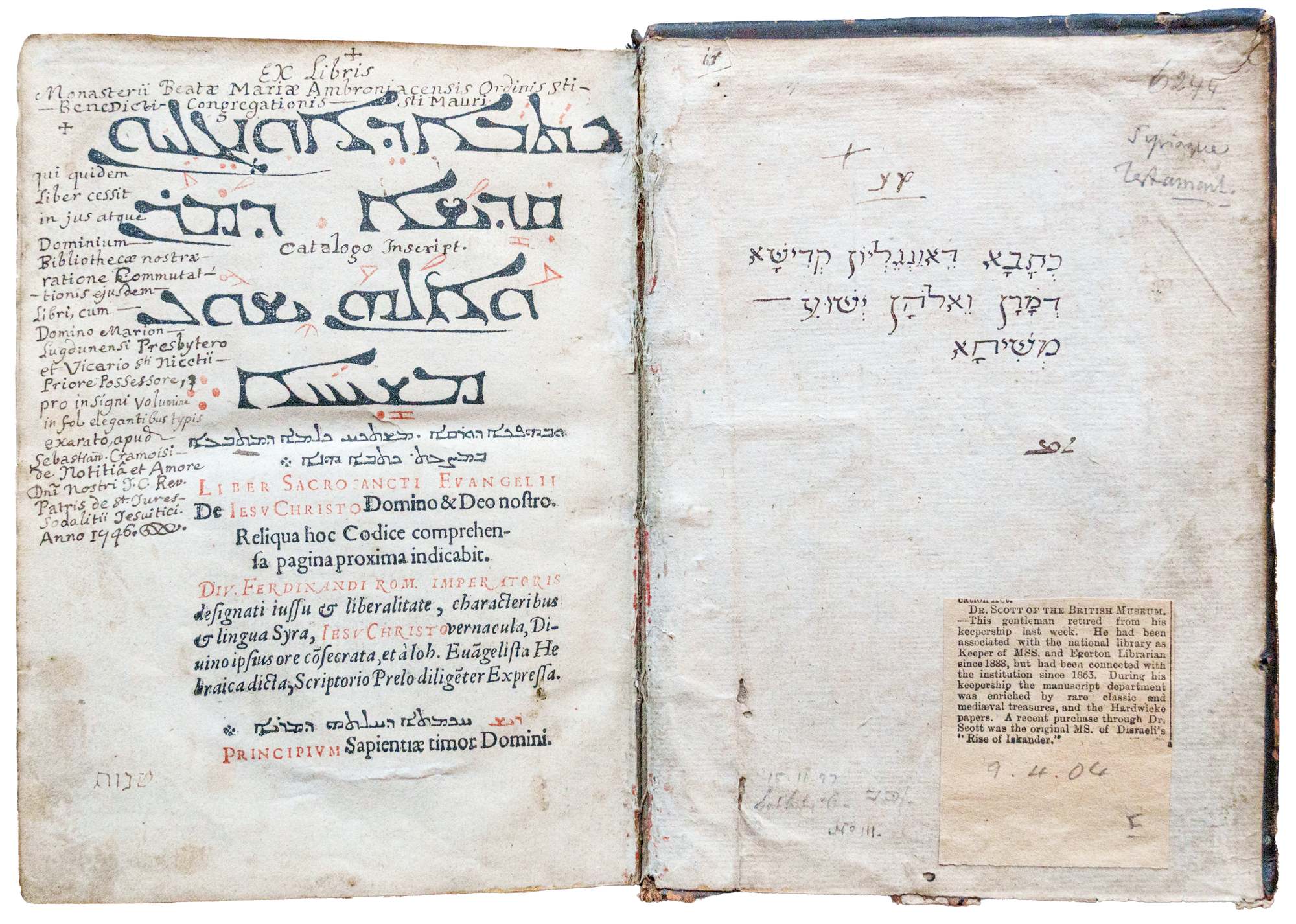

This very early bible is written partly in Latin but mainly in the Syriac language which is a dialect of Middle Aramaic once spoken extensively across a large area of the Middle East known as the Fertile Crescent.

It is an important treasure because of its great age and the role it played in the spread of Christianity in the Middle East.

Syriac is a dialect of Eastern or Middle Aramaic that was spoken in the early Christian period in the principality of Edessa, today part of northern Syria, Iraq and southern Turkey. It was a literary language, written in the same alphabet of 22 constantans as Hebrew but also with characters of its own.

Having first appeared in script form in the 1st century AD after being spoken as an unwritten language for centuries, Classical Syriac became the major literary language of the Middle East from the 4th to the 8th centuries and is preserved in a large body of Syriac literature.

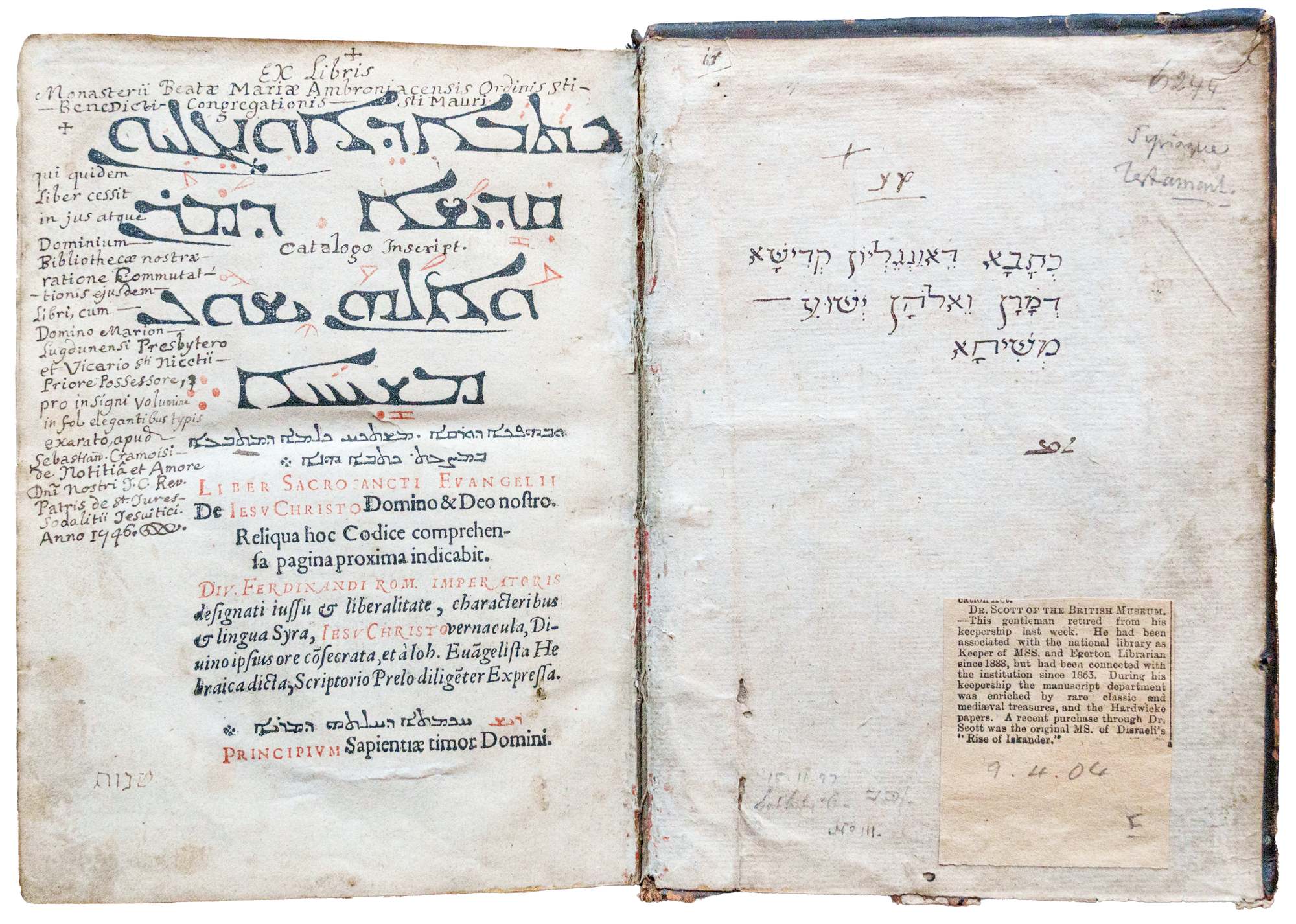

One of the previous owners of this bible was the congregation of St Maur, often known as the Maurists, a congregation of French Benedictines established in 1621 and known for their scholarship. Towards the end of the 18th century a spirit of freethinking and rationalism became wide spread and the congregation was suppressed and the monks disbursed before the Revolution with the last superior-general and forty of his monks dying on the scaffold in Paris.

RGSSA catalogue rgsp 225 B582

The title page of this Bible shows

Ex Libris

Marie Ambonica, Congregation St Mauri, anno 1746

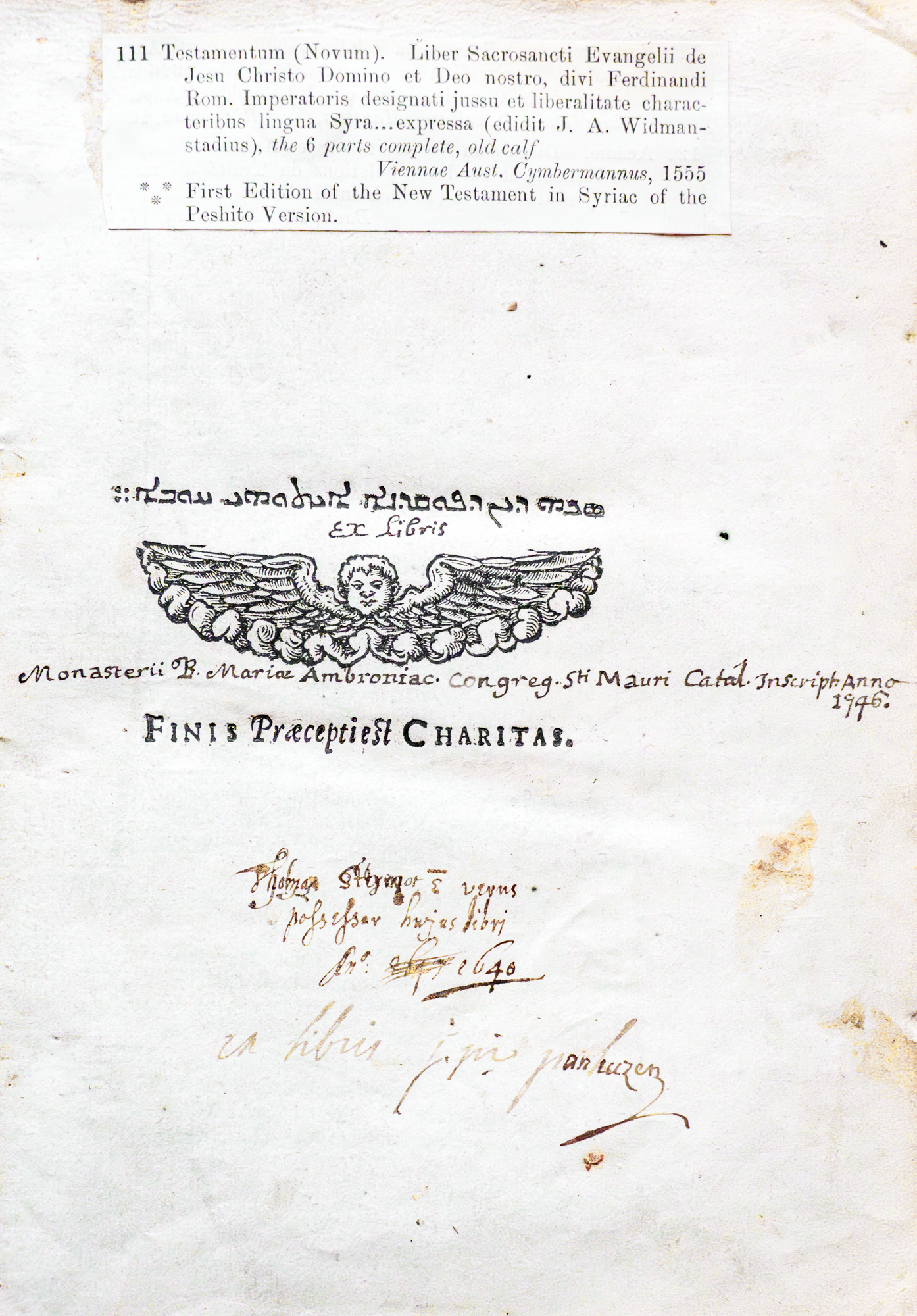

The following quotation is from the Angus Library and Archive* blog The Syriac Bible, 1555-

The first book printed in Syriac and the editio princeps of the New Testament in this language was printed in Vienna in 1555. It was edited by Johann Albrecht Widmanstadt (1506-1559) with the aid of Moses of Mardin, a scribe in the service of the Patriarch of Antioch, and dedicated to Ferdinand, King of Hungary and Bohemia, Archduke of Austria and Duke of Burgundy, at whose expense the work was published. Although ostensibly for Syriac-speaking Christians who were in need of a New Testament in their language, it was created partly as a missionary tool to convert Jews and Muslims in the East. It was also the product of a sixteenth-century humanistic interest in the Orient in response to the rising threat of the Ottoman Empire and the desire to go back to the roots of the Bible. According to Widmanstadt in his dedication to Ferdinand, who succeeded Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1558, more scholars were able to read Hebrew and Chaldean than ever before, which went a long way to undo the linguistic dispersal after the Babel episode. This edition had a print-run of 1000 copies of which 300 were taken to the Patriarch of Antioch. A second edition was produced by Michael Zimmermann (Cymbermannus) in 1562, after obtaining imperial licence to use the Syriac type.[1]It is mentioned in the 1611 English King James version as being in ‘most learned men’s libraries’ in the translators’ note to the reader.

* The Angus Library and Archive is "a leading collection of Baptist history and heritage worldwide."

© The Royal Geographical Society of South Australia